Portrait of a Young Gentlema Philadelphia Museum of Art

Essay

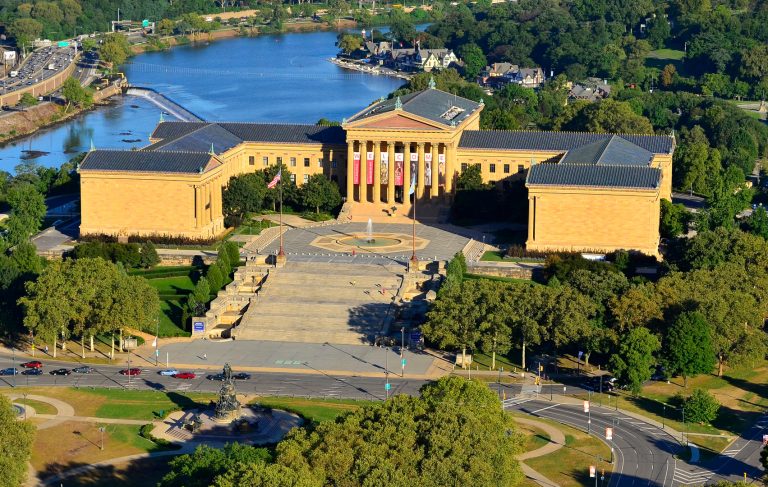

The Philadelphia Museum of Fine art—originally known every bit the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Fine art—adult from collections exhibited in 1876 at the Centennial Exhibition in Fairmount Park. Modeled on the South Kensington Museum in London, the new institution sought through both collections and classes to teach design and so that goods produced in Philadelphia would be more competitive with those made in Europe. By the 1920s, however, the museum shifted its emphasis toward cultivating elite sense of taste as it constructed a monumental new building, caused landmark collections, and courted wealthy patrons. With xc percent of its collection acquired from donors but also a longstanding, if failing, financial human relationship with Philadelphia's city government and the Fairmount Park Committee, the museum negotiated a tension familiar to nigh art museums between the aesthetic values of high-society collectors and a charitable mission to enhance public life through art.

The Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art was founded in 1876 and opened to the public in Fairmount Park's Memorial Hall in 1877, but members of the Fairmount Park Commission had discussed the idea even earlier. The Centennial brought the museum idea to fruition as members of the semiautonomous Park Commission, other metropolis officials, and appointees to the federally authorized Centennial Committee worked together to stage the Exhibition. A combination of the Park Committee, the City, and museum trustees continued to make decisions—and to complicate controlling—about the institution throughout its history.

The Museum and School of Industrial Art arrived at a moment of change both in American history and in the history of museums. The Centennial Exhibition, while celebrating the history of American independence, also promoted the country and the metropolis of Philadelphia every bit progressive, post-Civil War societies at the forefront of modernity and the Industrial Revolution. However, when Americans compared themselves to their European counterparts in science, industry, or art, they often feared they were defective. During this period, elites by and large designed museums as sites for the heart and upper classes to cultivate or prove their good taste. At the Museum and Schoolhouse of Industrial Art, however, the decorative objects retained from the Centennial were too a teaching collection viewed past working people—factory laborers, artisans, and industrial designers—who might be inspired to make and eat better, more beautiful industrial goods.

Much like the Academy of Natural Sciences (founded in 1812) and the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (founded in 1877), the Museum and Schoolhouse of Industrial Art organized its collections scientifically and systematically. Large glass cases in Memorial Hall displayed arrays of artifacts co-ordinate to part and material, progressing through time. Withal, over the adjacent few decades, the collections began to change. The 1893 heritance of Anna H. Wilstach (1822-92) to the Fairmount Park Commission and to the museum began the institution's move toward fine art. The paintings she donated were valuable, simply the $500,000 discretionary fund she left for purchases had fifty-fifty more dramatic impact. Over fourth dimension, the bequest led to almost grand acquisitions including innovative masterpieces by Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) and Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859-1937), an African American.

Prominent Philadelphia Donors

Other valuable collections of Western art followed in the early twentieth century, including those of William L. Elkins (1832-1903), an oil and transportation magnate, and his son George Due west. Elkins (1858-1919); John Howard McFadden (1850–1921), a wealthy cotton merchant; and John One thousand. Johnson (1841-1917), a lawyer for corporations like Standard Oil, Baldwin Locomotive, and United States Steel. These men—some of them too powerful Fairmount Park commissioners with vested interests in the museum already— officially bequeathed their collections to the urban center and the Park Commission, but the museum then cared for and exhibited them. All the donors were prominent Philadelphians and very wealthy, but also philanthropic and civic-minded. Johnson, whose collection of European Renaissance art was the biggest prize out of any acquired at this time, said in his will: "I accept lived my life in this City. I want the collection to have its domicile here."

Elkins and McFadden fabricated their bequests contingent on the creation of a new building to firm them, and further donations of collections made more space in a grander setting, closer to City Hall, a priority. Past 1917, the museum trustees and staff finalized plans to leave Memorial Hall for a new edifice on the most-completed parkway extending from Metropolis Hall to Fairmount Park. Horace Trumbauer (1868-1938), Paul Cret (1876-1945), and the firm of Zantzinger, Borie, and Medary designed the building collaboratively with labor by numerous others including perspective drawings by Julian Abele (1881-1950), a rare opportunity for an African American architect at that time.

In 1928, the eclectic Greek Revival building opened at a cost to the city of $12 one thousand thousand. Because the building sat on city land, the Fairmount Park Commission managed it with urban center funds. When seeking financial donations, some of the museum's leadership emphasized the new edifice as a affair of borough pride for all citizens. Yet for museum president Eli Kirk Price (1860-1933), such a monumental building also served to "encourage men who already have bought pictures to requite them to the museum." In the spirit of both cutting costs and encouraging Price's donors, the edifice was strategically constructed as a massive shell into which the museum could gradually build galleries for new collections. Those empty galleries could promise donors that their collections would non go into storage, simply they also became a promise that the city would not just support public space in its parks, but also elite sense of taste in its museums.

A New Organizational Scheme

Starting in 1925, director Fiske Kimball (1888-1955) oversaw the building of galleries and the donation and purchase of new collections, but he also implemented a new organizational scheme for the works displayed in the new building. The new exhibits were non a systematic array, but a history of art. The 2nd flooring used masterworks to evidence the evolution of European art from the Middle Ages to the modernistic era. Kimball also innovated in embedding period rooms that further illuminated this chronology. While other museums staged rooms to correspond specific times and places, Kimball began importing whole architectural elements to create context for furnishings and art. Combined with his floor-wide history of art, the museum became a "walk through fourth dimension" both within and across galleries. By the mid-1930s, Asian galleries in the S Wing housed art from Bharat, People's republic of china, Nippon, and Iran just offered trivial caption every bit to how they fit into the grand narrative and inevitable march of Western progress portrayed elsewhere in the museum.

The first floor, meanwhile, presented "study collections." In the South Wing, these more in-depth exhibits included displays of decorative arts that followed in the tradition of the original Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art. The works in the Northward Wing focused on specific eras and areas of Western art, merely tellingly, maps for visitors labeled the galleries by collector with discipline matter indicated in secondary text. Thus, while the South Wing'southward curation reflected the establishment's original educational intention, the arrangement of the North Wing, much like the compages of the museum, catered to wealthy donors. The new building independent these study collections, but it did non house the school. Although the ii were still officially continued, by 1938 the institutions became the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) located on the Parkway and the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art located on South Broad Street.

Despite the museum's dwindling relationship to the schoolhouse, other kinds of outreach extended to the public. Nether Kimball the museum founded a Sectionalisation of Didactics in 1929 and in 1931 opened a short-lived co-operative at 60-Ninth Street Terminal in conjunction with the Carnegie Foundation and a developer in Westward Philadelphia. Long-lasting affiliations that began in the 1920s included two Fairmount Park historic houses (Cedar Grove and Mount Pleasant) and the Rodin Museum on the Parkway. In 1944, the museum established some other enduring relationship past agreeing to administrate the Fleisher Fine art Memorial at 8th and Catharine Streets. Fleisher'southward free classes, unlike those at the School of Industrial Art, taught art as recreation not profession.

Progress Even During the Depression

Although non immune to the impact of the Peachy Low, the PMA completed dozens of galleries throughout the 1930s to house acquisitions such as the Edmond Foulc Drove of Medieval and Renaissance Fine art. Much of this construction occurred with help from New Deal programs like the Works Progress Administration. The museum besides gained artworks, peculiarly African American prints, from the Public Works of Art Project. While the PMA's finances suffered in the 1930s, it continued to spend, and some raised questions almost whether art was a worthy cause when so many people were out of work and hungry. Among those raising these questions in the early on 1930s were Mayor Harry A. Mackey (1869-1938) who, with Metropolis Council, controlled much of the museum's upkeep. Cartoonists at The Philadelphia Record echoed those concerns when the museum bought Cézanne'southward The Bathers for $110,000 in 1937.

During the Kimball era, the museum made huge acquisitions including an intact French Medieval cloister, but the emphasis on recreating the past concerned some who felt the museum was falling backside past not collecting more innovative modern art. The museum acquired some modern works—similar The Bathers and the photography collection of Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946)—in the 1940s. Information technology was later, in the 1950s, that the Walter and Louise Arensberg Collection—including many works past Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968)—and the A. E. Gallatin Collection (also known as The Museum of Living Art) established the PMA as a major repository of modern and contemporary art.

The Arensberg and Gallatin collections, donated from outside Philadelphia, demonstrated the growing reputation of the PMA and the work it contained. The Arensbergs, for example, selected the PMA because they believed their collection would be most valued and do the most good in Philadelphia. Some Philadelphia collectors, however, spurned the museum. Joseph Widener (1871-1943)—a Philadelphian who was heir to his father's transportation fortune and had longstanding, multigenerational connections to the urban center and the museum—slighted Philadelphia and in 1942 opted to enshrine himself and his collection at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. With the opposite motivation, yet like result, in 1922 Albert Barnes (1872-1951) created his ain educational foundation so his collection might be used to combat the elitism of the art world in full general and Kimball's PMA in particular.

The First Admission Fee, 35 cents

In 1962, the museum which was previously free began to charge an admission fee of 35 cents, but during that decade it also expanded its education programs for adults and schoolchildren, and in 1970 it created a Department of Urban Outreach (DUO). If the admission fee made the museum less accessible, programs similar DUO'south murals and other public works made it more then.

Throughout the 1970s, the museum responded to other trends in the museum world every bit well. It added visitor-centered civilities similar a restaurant and air workout. It also began hosting more blockbuster shows featuring recognizable artists like Duchamp and Vincent Van Gogh (1853-90). Nevertheless, the PMA was more than often an early adopter than an innovator. Although the museum's founding as a school for industrial designers once set up it apart from institutions like the Metropolitan Museum of Fine art in New York, past 1964 the school officially separated from the museum, eventually becoming known as the University of the Arts.

The d'Harnoncourt Era

In 1982, Anne d'Harnoncourt (1943-2008), a Duchamp scholar and longtime modern art curator at the museum, became director. She continued to build the modern and contemporary collections with major acquisitions by artists such every bit Cy Twombly (1928-2011) and Bruce Nauman (b. 1941). She also acquired the Muriel and Philip Berman Collection of prints and drawings by erstwhile masters and presided over a 1989 legal victory that allowed the Johnson collection to be integrated into the collections at big. This led to reorganizing the European art galleries in an fifty-fifty more monumental narrative of Western masterpieces that better realized Kimball'south vision of exhibiting the paintings as a walk through time and a march of progress. While more spectacular according to many standards because of the quality of the work, the exhibits changed piffling most the standard narrative of art history. In contrast, the African American Collections Committee, created in 2001 for the museum'southward 125th anniversary, made the collections more inclusive past purchasing works that filled gaps where other donors failed to collect.

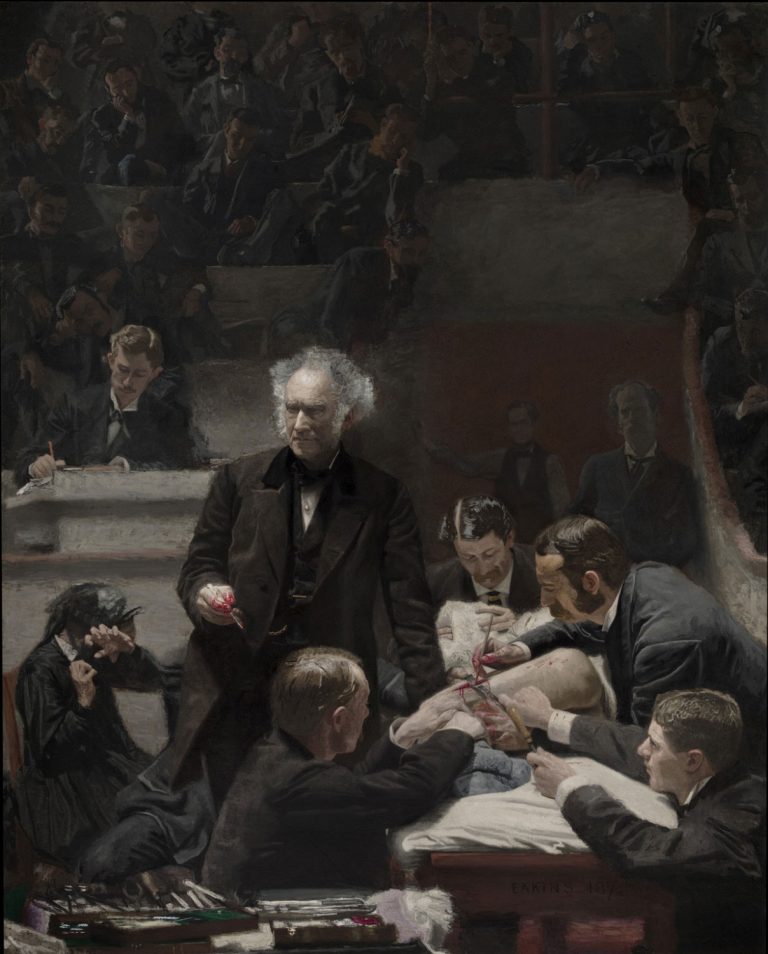

In many ways, d'Harnoncourt continued in the tradition of Kimball equally she expanded the reputation of the PMA and Philadelphia as an elite eye of fine art collecting and exhibition. The $68 million joint effort with the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 2007 to purchase Thomas Eakins' (1844-1916) The Gross Dispensary when Thomas Jefferson University wanted to sell information technology epitomized a dedication to fine art and the urban center at a time when the city was perpetually on the verge of bankruptcy and investing less and less in its cultural institutions. Nevertheless the Gross Clinic campaign to keep the iconic painting in Philadelphia also showed commitment to an art earth steeped equally in money and taste every bit in public service and inclusive civic pride. Likewise, the addition of the Perelman Building on Pennsylvania Artery primarily provided more than space for existing collections, although it also held the hope of being a more flexible and more than community-oriented space than the museum'southward main temple on the hill.

Plans for an expansion designed by Frank Gehry (b. 1929) began during d'Harnoncourt'south tenure, so commenced construction in 2017 under the directorship of Timothy Rub (b. 1952). Information technology continued projects undertaken since the 1970s to make the museum more welcoming to visitors, especially those with cars, and easier to navigate both inside and out. At the same time, digital initiatives and educational outreach promised to expand the accomplish of the museum in ways that paralleled earlier efforts to create audio guides for the galleries, develop curriculum for schools, and provide altitude programs through teleconferencing and telephones.

The Iconic Museum Steps

The museum, a home to 240,000 priceless objects and an ongoing recipient of funding from the urban center which endemic its building, e'er identified itself every bit a civic establishment for Philadelphians. This extended to the museum's virtually visible public infinite, the iconic seventy-two steps leading up to the museum's Parkway-facing entrance. With a spectacular view of City Hall down the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, the steps became a must-run into attraction for tourists, the lead-in on sports broadcasts and other televised events, and autograph for the city in popular media. However, this was every bit much because of Rocky Balboa's preparation montage in the Oscar-winning film Rocky (1976) every bit information technology was because of John Johnson or Fiske Kimball. Instead of creating literal common footing betwixt aristocracy, private benefactors and a broader public, a contend emerged over where the statue of Rocky donated by player and star of the picture Sylvester Stallone (b. 1946) should stand. Many at the museum argued that information technology was a picture show prop, non properly art, and the statue spent years at the Spectrum loonshit in South Philadelphia before being placed not at the top of the steps simply at the bottom in 2006. This was revealing of how the museum negotiated the interests of different audiences who sometimes struggled to observe common ground in fine art, specially when the icons of one form could be pushed to the side to legitimate those of the other.

Despite the snub of Rocky, the PMA embraced more accessible, community-driven interpretations of its collections and the broader role of the art museum. A cheeky advertizing entrada from 2017 featured nonchalant company commentary—Botticelli'due south Portrait of a Young Human was captioned, "I recall he'south throwing some serious shade"—that sanctioned laughter at the obscurity of loftier cultural sense of taste. Even more progressively, the "Philadelphia Assembled" exhibit, as well in 2017, combined art and civic engagement. As an instance of the museum'south efforts to become more than politically relevant to a changing gild, the showroom gave infinite—admitting only at the Perelman Edifice—to individuals and organizations to create stories of resistance and community building, challenging the cultural hierarchies of the by and sharing authority with a more inclusive customs.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art in most ways fit the paradigm of the encyclopedic art museum as information technology had existed in Europe and North America since the nineteenth century. It had unique origins in teaching and industrial design, but information technology quickly fell into the patterns of like institutions that showcased awe-inspiring narratives of Western art. Over time it became more than inclusive with programs to sponsor public fine art and to acquire and exhibit more than art by women and people of color, although funding, purchases, and outreach programs to nether-served communities could only begin to address the history of an institution whose world-renowned collection reflected the hierarchical tastes of elite donors and curators. Past the twenty-get-go century, exhibition and program strategies sought to mobilize the museum and its collections in multiple and sometimes surprising means, despite the heritage they most visibly embodied.

Mabel Rosenheck is a author and historian in Philadelphia. She received her Ph.D. in media and cultural studies from Northwestern University and works at the Wagner Free Institute of Science, Temple University, and elsewhere.

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Philadelphia Museum of Fine art Online Collections Search

- Ghost Station At Art Museum Rises From The Expressionless (Hidden Urban center Philadelphia)

- Philadelphia Museum of Art Photographs, 1928 (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Around the Philadelphia Fine art Museum (Association for Public Art)

- Diana of the Tower (Hidden Urban center Philadelphia)

Source: https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/essays/philadelphia-museum-of-art/

0 Response to "Portrait of a Young Gentlema Philadelphia Museum of Art"

Postar um comentário